Sabotaging the Miracle Machine: The High Cost of Luddite Policies

Technophobia has a body count and a rash of fear based precautionary principle legislation is crushing the west's historical innovation machine

Imagine a very different 2025:

You can hop on a supersonic plane and get from New York to Los Angeles in 30 minutes or New York to Japan in 2 hours instead of 20. There is no climate crisis or activists gluing themselves to famous paintings. Stem cell therapies for damaged hearts came a decade earlier and saved tens of millions of people from early death.

We've got tremendous energy abundance with cheap, clean, nuclear energy and sweeping fields of solar cells with batteries. Machine learning solved protein folding 20 years earlier and powered a medical revolution, with permanent CRISPR cures for cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anemia. There are mRNA cures for breast and prostate cancer, nanotech robots that eat arterial plaque, robotic factories building everything from toys to advanced chips. A grid of 7th gen Starlink satellites beams down InfiniBand speed internet across the globe so a top doctor in New York can perform life-saving surgery via robot halfway across the world in ultra-high definition VR with no lag.

How did we get to this sci-fi future decades early? In our alt-history, the Luddites and the enemies of progress failed at every attempt to cripple, crush, or kill progress.

There was no backlash against "sonic booms" or runaway fears after the Concorde explosion. Instead, engineers did what they did with every other plane: they made them safer. As USA Facts tells us: "In 2022, there were 47 passenger injuries over 709 billion miles of air travel — you could circle the globe over 600,000 times for every one airplane injury."

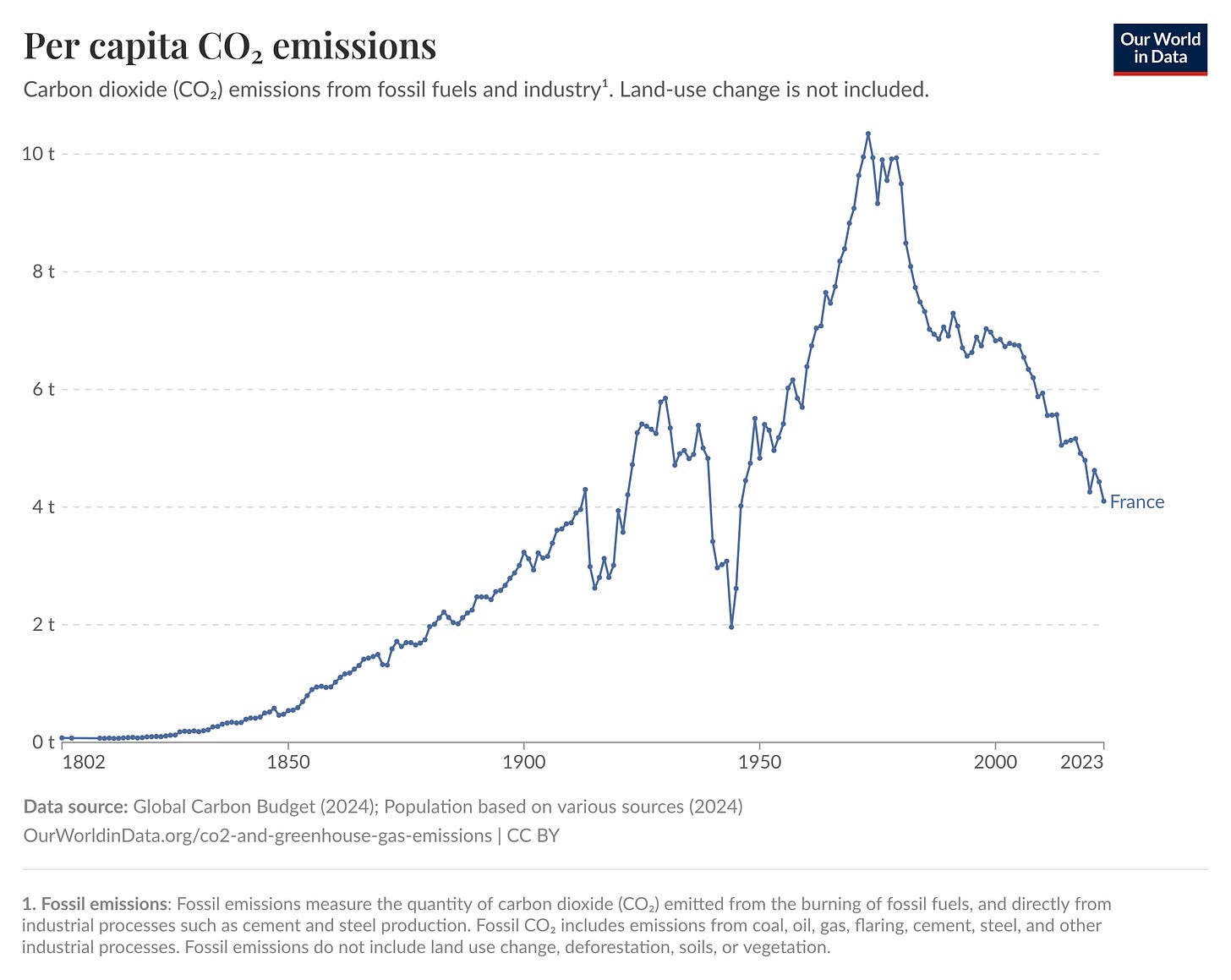

Instead of hitting the kill switch on nuclear in the 1970s, the US kept right on building reactors and now we have an emissions chart like France, and so does the rest of the world. We've got safe, clean, abundant energy and there's no talk of degrowth or slowing down, just what to build next.

(Source: Our World in Data: French emissions chart over the last 120 years)

We didn't pull funding for stem cells in the Bush administration, and US and European activists never went on a pogrom against GMO in Africa after they already benefited massively from food abundance. Anti-nuclear activists didn't kill the American nuclear expansion in the 1970s.

Unfortunately, that's not the world we got. What went wrong?

The answer is that in way too many cases, the Luddites won.

(Ned Ludd the fictional leader of the Luddites)

They slammed the brakes on technology and progress out of blind animal fear and we all pay the price. The hidden price of technophobia is incredibly high. The real cost of these doomsday policies is in the air we breathe, the families who bury loved ones too soon, the new kinds of jobs that never get created, and the rockets that never blast off.

Activists always push big, scary headlines about what we're going to lose—a silent spring, massive unemployment, a new ice age—but they never talk about what we lose: the jobs that never get created, the clean air we don't breathe, the cascade of new inventions that never come to be.

When you throw a wrench in the wheels of progress, opportunities disappear in an alternative future that never happens. Enemies of innovation always think they're on the side of the light by slowing things down. But they never think about the side effects, about all the good things that we miss out on when we gum up the works. What diseases will we cure with stem cell breakthroughs decades later because we wasted eight years in the Bush administration restricting the research?

Opportunity cost is invisible—but it's one of the biggest bills in history.

The Clean‑Energy Future We Threw Away

Picture the United States in 2025 running on a French‑style nuclear grid: 70‑plus percent of electricity from zero‑carbon fission. The NASA Goddard/Hansen study calculates that the nuclear fleet we did build has already prevented 1.8 million premature deaths and 64 gigatonnes of CO₂ since 1971.

Now double or triple the size of our reactor fleet instead of activists and regulators strangling nuclear acceleration. We would have prevented another two to four million deaths and held temperature rises almost flat.

In short, there'd be no climate crisis and no talk of one.

Instead, we didn't break ground on a single new reactor between 1977 and 2013, and the first of them didn't go online until 2023, and two of the four were abandoned before completion.

Three Mile Island was the ultimate catalyst that scrapped the Atomic Energy Commission and replaced it with the practically anti-nuclear Nuclear Regulatory Commission. The NRC prioritized slowing down and throwing roadblocks up at every turn. Why? Because humans are great at overestimating big, flashy, short-term threats and completely failing to see long-term ones and what gets lost when we take one path versus another. It's easy to see a sunburn and realize you need more suntan lotion the next time, but getting lung cancer from smoking doesn't happen for decades, and so it's easy for people to puff away without awareness of what's coming down the pipe.

When it comes to Three Mile Island, nobody died. The worst dose at the fence line was less than a chest X‑ray. But that big, scary, near-miss event became the rallying cry that iced nuclear builds for forty‑six years. While the U.S. fought over paperwork, coal plants kept belching. Air pollution still kills every single year.

The body count of inaction dwarfs Chernobyl, Fukushima, and every other nuclear incident combined.

Ironically, you can blame the climate crisis on climate activists from the 1960s. Trace the results from their anti-nuclear activism and you get a direct connection to a warmer planet.

Again and again throughout history we've seen Luddites crush the future, and every time it means at its best lost time and opportunity, and at its worst, disease and death.

Eight Years in the Stem‑Cell Wilderness

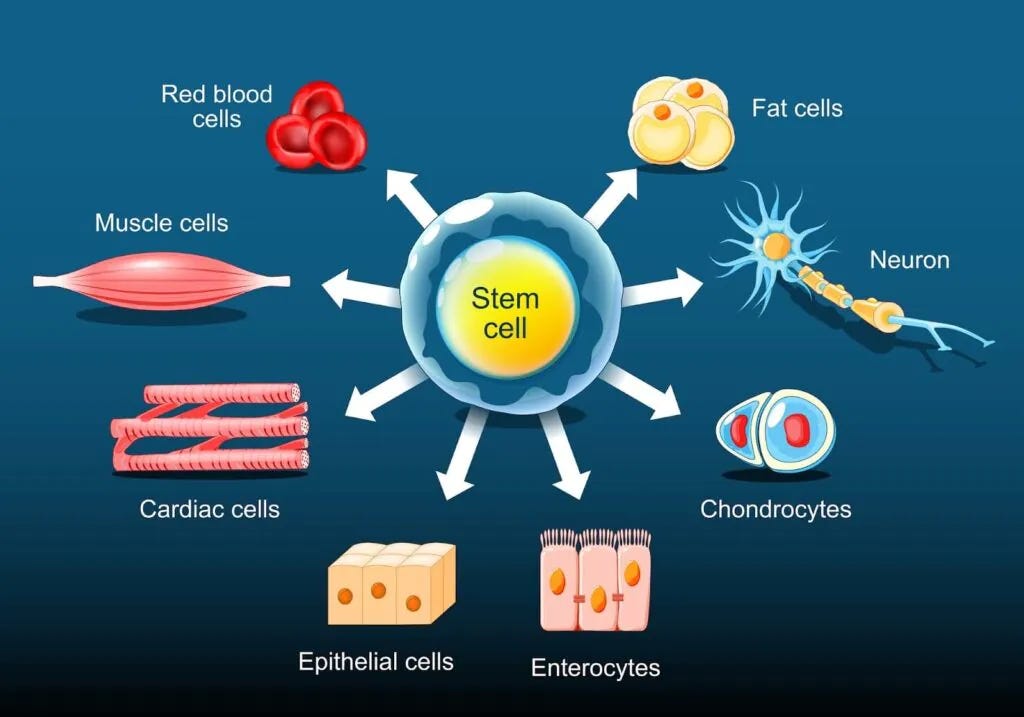

Stem cells hold promise for treating everything from heart disease to badly burned skin. Heart disease kills 17.9 million people every year. Currently, there's no way to treat a damaged heart, to heal scar tissue, or regrow damaged parts of your heart. You're stuck waiting for a heart transplant. Transplants aren't scalable. There are only so many donors, and wait lists grow every year. Badly burned skin requires skin grafts. They also don't scale.

Imagine if we could regrow skin and heart tissue?

(Source: Swiss Medica)

Trials are already underway. In 2024, a University of Illinois cardiologist advanced stem cell therapy for heart failure to clinical trials, the first U.S. test of umbilical cord-derived intravenous delivery stem cells in patients for chronic heart failure.

But that's just the treatments of tomorrow. Stem cells are already used to treat everything from broken bones to blood disorders like sickle cell anemia and leukemia after chemo damages bone marrow.

It could have happened a lot faster.

In August 2001, President George W. Bush froze federal funding for embryonic stem‑cell lines. Overnight, America's most promising biologists became policy refugees. Labs shuttered or limped along on private grants; many simply moved to Singapore and the UK.

The embargo ended in 2009, but in science every lost year compounds: fewer post‑docs trained, fewer papers cited, fewer spin‑outs launched, fewer breakthroughs built on the back of other breakthroughs. A paper published in the Journal of Technology and Innovation on macular degeneration and Type 1 diabetes in 2011 estimated that the moratorium delayed first‑in‑human stem cell therapies for by at least five years, affecting countless patients who could have regained their eyesight or thrown away their insulin pumps earlier.

California tried to fill the void with a $3 billion bond, but even that couldn't replace a decade of coordinated federal effort.

Those delayed and missing therapies are an unmarked graveyard of vision, mobility, heart attacks, cancer, and time.

The Empty Fields of Africa

American and European activists enjoy organic kale while lecturing African farmers to avoid "Frankenfoods." The result? Vitamin‑A deficiency still blinds half a million children a year. Golden Rice—the GMO that fixes the deficiency—was ready in 1999. Twenty‑six years later, Philippine courts suspended rollout "out of caution," and most African regulators followed suit.

(Source: A scientist shows "Golden Rice" (R) and ordinary rice at the International Rice Research Institute in Los Banos, Laguna south of Manila, August 14, 2013. REUTERS/Erik De Castro)

Banana Xanthomonas Wilt (BXW)gene‑edited banana remains a massive problem for farmers across Africa, in lives and livelihoods. It slashes yields and sometimes kills as much as 100% of a farmer's crop. A single variety saves the crop, but adoption remains stuck below 2 percent because seed regulators haven't cleared it.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons, bananas ravaged by Wilt)

Smart bills to intelligently regulate GMOs get stuck in endless back-and-forth battles. Kenyan cassava, Nigerian cowpea, Ugandan banana—each sits in a regulatory holding pattern while real people skip meals. Genome‑editing could double smallholder yieldsget stucklate-2019 approval and erase entire pesticide classes, but smart bills to intelligently regulate GMO crops in endless back-and-forth battles.

A disease-resistant cassava in Kenya, a vitamin-A-fortified banana in Uganda, a blight-resistant potato in Nigeria — each sits in a regulatory holding pattern while real people skip meals. (Though in a recent glimmer of hope, Nigeria did make some progress with the of pod borer resistant cowpeas.)

According to a paper published in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotech, this is largely due to Africans' ingrained resistance to food innovations:

"Africa has historically struggled to adopt innovative agricultural technologies, which has significantly hindered efforts to ensure food security and improve livelihoods over the past century. A major obstacle in this regard has been the persistent skepticism surrounding the potential benefits of agricultural biotechnology.

The challenges contributing to this skepticism include a notable knowledge gap among stakeholders, widespread technophobia, or fear of technology, as well as inconsistencies with global agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). Although these challenges are not exclusive to Africa, they disproportionately impact the continent, making the need for effective solutions even more urgent."

But it wasn't just homegrown fears. Instead of genuine safety concerns, what really stalled progress was an NGO-orchestrated scare campaign out of the US and EU. In his article A Dubious Success, the NGO Campaign Against GMOs, Robert Paarlberg, a professor of political science at Wellesley College, details how Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth International, and others recast safe, field-tested GMOs as "hazardous wastes" during the Cartagena Protocol talks — terrifying African delegates and trapping lifesaving crops in endless red tape.

It's the same story again and again in history. Activists trumpet the possibility of hypothetical risks while ignoring the certainty of hungry kids.

All of those are happening in the past, but what about the future of Luddite policies?

The mRNA Backlash

mRNA flipped the lights on during the COVID pandemic. Now the same tech is in late‑stage trials for HIV, Zika, and cancer. You'd think we'd be celebrating the potential end of these dreaded killers, but instead we have a small contingent of radicals fighting to .

How did it happen? Mostly because of Operation Warp Speed and the intense politicization around the COVID pandemic. Operation Warp Speed was one of the most incredibly successful technological acceleration projects in history, but it has the dubious distinction of being largely disavowed by both the left and the right — by the left because it came under Trump’s first administration, and by the right because of growing distrust toward health authorities during the pandemic.

But Operation Warp Speed was massively successful. It saw the US deliver a vaccine in 9 months and reach 40% coverage in the first year, instead of a decade.

As James Pethokoukis wrote in The Conservative Futurist:

"America was the first nation to roll out a vaccine. And it did so rapidly, getting the COVID-19 vaccine to the American people in less than ten months. And it wasn't just a single vaccine. Operation Warp Speed delivered three in record time...[D]rug companies had lost money during previous public health emergencies, such as the 2014 Ebola outbreaks, when treatments they developed turned out to be unnecessary. But now we needed those companies to make numerous big and bold—and risky—bets. So Operation Warp Speed placed orders for vaccines and therapies while still undergoing clinical trials, regardless of the outcomes. This encouraged pharmaceutical companies to expand manufacturing capacity so vaccines and therapies were ready to be distributed once they had the FDA's green light."

But it looks like instead of people cheering a promising HIV vaccine, we've got people fighting the most prominent trial because a few trial participants developed treatable hives. Who wouldn't take hives over dying of AIDS? Every known treatment has some kind of minor side effect. We push forward with them because the disease is worth fighting anyway. Instead, congressional firebrands drafted "mRNA moratorium" bills and NIH pulled co‑funding for the HIV vaccine program.

Freeze the pipeline today and you don't just delay vaccines; you kneecap the entire platform. Every postponed trial means the next generation of lipid nanoparticles, dosing algorithms, and delivery devices never arrive. That cascades into oncology, gene editing, even protein replacement.

The ladder of progress doesn't let you skip steps: kick out the first rung and you never reach the top.

We've Seen This Movie Before and the Great Chain of Creativity

Technophobia is the oldest genre in history:

1450s – Scribes smashed Gutenberg presses and chased printers out of town.

1840 – Painter Paul Delaroche saw the first daguerreotype and declared, "From today, painting is dead." It wasn't. It evolved.

1930s – The American Federation of Musicians tried to outlaw "talkies" because recorded soundtracks killed the pit‑orchestra gig.

Robots have been about to take all the jobs for 100 years.

Every time, folks say "this time is different." Every time, it's a rerun. We adapt. We change right along with our technology.

We've always adapted our lives, culture, work, labor and business in the face of new technology. Technology isn't something that's outside of us. It's a part of us, a part of who we are as human beings. We're a long line of problem solvers and engineers. Ever since we fashioned sharp stones on sticks to make axes, we've constantly changed how we work and play and survive.

The tech rises and diffuses, culture adapts, creatives find new ways to be creative and humanity levels up.

Progress is recursive. Each step builds off the last step.

Once you have the ability to make clear glass, you get eyeglasses. Once you get eyeglasses, you get the microscope — a Dutch eyeglass maker created that modern marvel of science after seeing his kids playing with two lenses to magnify things.

A fabric maker then used the microscope to look at fabrics and saw a whole world of tiny creatures we didn’t know existed. Once you have an understanding of microbes, you get germ theory and the ability to fight infections.

Transistors enable personal computers; PCs enable the internet; the internet trains large‑scale AI; AI accelerates protein design; and protein design feeds back into better medicines and smarter biomaterials that improve the next generation of processors.

Break any link and the whole chain stalls.

"If not for funding for my early work in deep learning from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which disburse a good deal of U.S. research funding, I would not have discovered lessons about scaling that led me to pitch starting Google Brain to scale up deep learning. I am worried that cuts to funding for basic science will lead the U.S. — and also the world — to miss out on the next set of ideas," writes Andrew Ng in a recent blog post.

Kill basic research for a decade and you don't just lose ten years. Pass restrictive laws out of fantasy fears of AI killing us all and you do untold damage to the exponential curve.

When regulation works, it creates minor speed bumps. It doesn't set up concrete walls. It demands proof of harms instead of imagining a whole host of harms that haven't actually materialized in reality and may never materialize.

You make things safe by building them, testing them, breaking them, and iterating—never by outlawing the lab itself.

As James Pethokoukis wrote for the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), if U.S. regulation had merely frozen at 1949 levels, today's GDP would be $54 trillion instead of $27 trillion. That's two extra American economies left on the table—money that could fund universal clean energy, cancer cures, carbon capture, and Mars colonies.

Opportunity cost isn't hypothetical. It's the difference between ten million spinal cords repaired or not, between two extra degrees of warming or not, between poverty and plenty for half the planet.

That's why the next decade has to belong to the builders.

We didn't get flying cars because we chose paperwork over propulsion. It's time to choose differently.

The cost of Luddite policies is too high to let them keep robbing us all of the future.

The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.

All good... except that there us no climate crisis. The alarmist- biased IPCC does not see one.

Too many forces go against new technology. Unfortunately, these forces aren't likely to change. It starts with an anti-intellectual push in this country lead by the current party in power. Add in religion, misinformation of the worst kind, rampant self-inflicted ignorance, and too many people making too much money the way things are today (see oil industry), and WAY too much money in politics.

Your rosy picture is directionally correct, though using all new technology for its own sake isn't always the best either. That said, I do like your direction!