It started with a simple letter to halt all LLM development, signed by some professional scare mongers, doomsayers and some very smart folks too. In a few days, it managed to turn into "it's not enough to stop all LLMs we've got to shut it all down forever" and bomb any “rogue datacenters by airstrike."

Suddenly, we'd jumped the shark from a semi-plausible (if not very useful) proposal to tin-foil hat land.

How did we get there?

Turns out we were there all along.

People have always been obsessed with the end of the world. We like to be afraid. We like big, scary visions. The Gods smiting us. The end times of Revelation. Meteors from the heavens. Aliens wiping us out. It makes for great literature and great summer popcorn movies.

But it doesn't make for a good take on reality.

My father always says "what we focus on expands." Focus on eating well and working out and your life becomes a self-sustaining loop of longevity, vitality and energy. Focus on everything to rage at in the world and you’ll probably end up popping pills constantly just to keep going while your health collapses out from under you.

The more you focus on the end of the world, the more likely it seems.

You study the Dark Arts and start seeing Dark Wizards around every corner, like Mad Eye Moody in the Harry Potter series. You're always looking over your shoulder. You misinterpret everything you see through that darkened lens.

You start to become convinced that it's not just remotely possible for the world to end in fire, it will end in fire. And we've got to stop it before it's too late! You become evangelical about it, heralding it from the tree tops, screaming to anyone who will listen. Suddenly, a remote possibility becomes an inevitability. The apocalypse is nigh!

You become Churchill's definition of a fanatic, someone who can't change their mind and won't change the subject.

Of course, the problem is really just a classic sampling error. Take this image below that every student of statistics knows by heart.

In World War II, they were trying to make planes stronger, by adding armor where they were most likely to get shot. So they studied all the planes that came back with holes. Seemed like a good idea until eventually someone realized they needed to study the planes that didn't come back, not the ones that survived. They focused on one thing and missed the real answer. They had to armor all the parts that didn't get shot, because those were the vulnerable parts.

It's a bit like Hans Rosling, the famous statistician, who once said that "You can choose to show only my shoe, which is very ugly and only a small part of me. News outlets only care about the small part and call it the whole world."

There are a million examples like this in life. In one of Robert B Parker's Spencer mystery books, Spencer meets an exclusive madam who tells him that a high-end escort has all the evidence in the world to think real love doesn't exist. She sees cheating husbands and people who don't care about connecting at a deeper level. But it's the same problem. Real love does exist, it's just not showing up in the men she's meeting.

Of course, it goes beyond sampling errors and spending too much time studying the Dark Arts. It's really the certainty about the end of the world that's the biggest problem with the AI doomsday cult and other cults like them.

You may have done some sound, even plausible reasoning about how artificial super intelligence may wipe us all out but you're reasoning with only the tools we have now and that doesn't really work. You can't see all the inventions that might mitigate the problem in the future. It's like seeing the first Wright Brothers’ flight and thinking well, we've never make something fly for a long time that can hold a lot of people with some wooden bodies and paper wings! You're right but you missed metal alloys and jet engines because they don't exist yet.

The truth is, nobody can see the future. That may sound like a stupid thing for a futurist to say, but it's true.

As a futurist I'm great at seeing the short range future and what's coming around the corner. I saw the internet as a massive, world shaping technology early and started working at an internet company during the pre-dot com boom when people thought the internet was still mostly worthless. I went to work in Linux when a recruiter told me all the jobs were in Solaris. I told him Solaris wouldn't exist in ten years and he looked at me like I had two heads. In 2014, while at Red Hat I wrote a manifesto that AI would change the world and we needed to be a part of it because we had the best chance of building the infrastructure to run it all. Spoiler, they didn't see it and didn't listen and now other open source software not built by Red Hat runs the MLOps platforms of today.

But what I can't do is see the medium term future, say 50 years out and we certainly can't see 100s or 1000s of years out. Nobody can. Don't get me wrong, it's fun to try and I've done it with my three part essay "AI in 5, 50 and 500 Years", but in 500 years it will almost certainly look pretty ridiculous. That's because on a long enough timeline, new inventions change the trajectory in ways we could never imagine. Anyone reading my predictions 500 years from now will think it's about as accurate as someone from the 1500s writing about 2023. I will have missed dozens or even hundreds of different game changing inventions and new social structures and political movements that radically alter the shape and substance of the world.

Think about some of the world altering technologies of the past.

Who could have seen all the things the printing press would unleash?

It led to the industrial revolution and the scientific revolution and a book in everyone's hand that covered everything from cooking to schlocky mysteries to programming. It brought down the church as the dominant political force in the world. It took us from a place where the average educated person thought witches caused storms and murder weapons would bleed when they were near a murdered body, to a place where we can usually predict the weather with high reliability in the short term and where we can fly through the sky in the belly of great machines and where fingerprints actually help catch murderers.

(Source: Midjourney, Prompt: a witch causing a storm —v 5)

Of course, it wasn't all good. It contributed to darkness too. Hitler and Mao were able to spread the word on their twisted philosophies and sweep up whole societies into war and suffering. The writer of the Anarchist Cookbook tried to get all copies of his book destroyed after growing up and realizing it wasn't a great idea to teach people how to make bombs, but the damage was already done and it's still in print today.

Still, on the whole the printing press and books delivered tremendously positive change. They single handedly leveled up the knowledge and intelligence of the whole world. If you could go back in time and change anything you want, how many people would choose to delete the printing press and take us back to poverty, ignorance and warring kingdoms?

And if you're trying to predict the future right before the printing press is invented? Even more impossible and fruitless. As soon as it comes into existence, all your predictions are totally smashed and you'd have to start from scratch to take the new technology into account. That shows you that even short term predictions can prove totally wrong.

The very existence of a bold new tech changes the trajectory of everything that comes after it.

It's like a stone hitting another stone mid-flight.

As economist and author, Tyler Cown writes, "The reality is that no one at the beginning of the printing press had any real idea of the changes it would bring. No one at the beginning of the fossil fuel era had much of an idea of the changes it would bring.

No one is good at predicting the longer-term or even medium-term outcomes of these radical technological changes (we can do the short term, albeit imperfectly). No one. Not you, not Eliezer, not Sam Altman, and not your next door neighbor.

How well did people predict the final impacts of fire? We even have an expression 'playing with fire.' Yet it is, on net, a good thing we proceeded with the deployment of fire (“Fire? You can’t do that! Everything will burn! You can kill people with fire! All of them! What if someone yells “fire” in a crowded theater!?”)."

Well, Hold On Just a Second, Maybe We Can

Now that I've just spent a bunch of time talking about why we can't predict the future all that well, I'm going to add a wrinkle that shows how and where we can.

There's one technique that works very well to help us see what's coming over the long term.

If we can't predict how specific technologies will manifest in the real world, or exactly how the next 50 or 100 or 500 years will play out, what can we do?

We can look at broad patterns of history and lean on those as a way to light the path forward better.

When it comes to technology there is one clear pattern in history. Humanity has always adapted to and integrated new technology. Always. Every time. As in a 100% success rate. That doesn't mean there are not short term bursts of disruption and chaos and change. But in the end, humanity morphs with its technology and reorganizes around it.

Of course, as they say in stock trading, past performance is not indicative of future performance, but sometimes it really is because we're leaning on 2 million years of history here. If I'm a betting man, I'm betting on the past performance this time. With the stock market, stocks have a history of going both up and down chaotically and at any time. That's the pattern and hence the rule not to bet on past performance of an individual stock.

But when it comes to humans and technology, we've successfully integrated fire, the steam engine, the first and second agricultural revolution, the scientific revolution and everything that comes with it, like gene editing and biotechnology, the industrial revolution and more. Electricity. The printing press. Air conditioners. Satellites. TV. Radio. Cars. Trains. Planes. Cell phones. The shovel. The flywheel. All of it.

Again, humanity has always adapted to new technology. Always. Again and again, we've created new technology, and doomsayers have told us the world is ending, and yet the world goes on.

We wiped out some of the old world jobs and created a massive array of new ones in their place. Today, we have more jobs than ever, not less. They're more varied too. Predictions of the end of the world have a zero percent success rate since the time of Nostradamus and Oracle Bones in China, right up to Heaven's Gate and Jonestown.

Sure, something might eventually wipe us out. Almost certainly. That's a big pattern of nature too. There might come something we simply can't adapt to in the future. The Trilobites are gone and so are the dinosaurs. But it wasn't tech that wiped them out, it was a natural phenomenon. Climate change. Boulders from heaven. I always say when it comes to something like climate destruction, the Earth isn't in trouble, we are. The Earth will happily delete us and sleep for two million years and evolve a more interesting species the next time around.

But when it comes to tech, I go with the big abstract pattern that says humans are tremendously adaptable and we'll adapt right along with this new technology too.

But aren't our intelligent machines out of control already, you whisper? We don't understand them. They're black boxes. They hallucinate and make up answers. They lack grounding in the real world. They have rapid improvements and experience exponential growth.

How can we possibly deal with all that?

The same way we always have.

In the real world.

Fixing Problems Outside of Fantasy Land and Finding Uses Too

As it happens, we can only fix problems in the real world.

We can't do it by imagining them all beforehand because whatever we imagine just won't be what happens in actual reality. We have to embrace new technology, find its flaws and fix them as they develop. That's what we've always done and it's always worked well.

Take something like refrigerators. We put out refrigerators and suddenly people didn't need to go hack ice out of lakes and ship it around the world. You could simply make ice with a machine and that meant food supply chains got longer lived and more stable because food could last longer. You can get berries and out of season vegetables in any country at any time of year because of the cold. They can grow them in hot houses and ship them to you in cold containers on ships.

But they weren't perfect. Sometimes the gas in those early refrigerators got exposed to the air through a leak and they had a tendency to blow up and cause fires when mixed with oxygen. That was a pretty big downside to that technology, as you might imagine, in an era of mostly wooden houses and cities.

Today, you'd have people screaming that refrigerators are too dangerous and we need to stop them now and why can't everyone just use natural ice anyway!?!?

But on the whole, artificial cold changed society for the better and in many ways nobody could have predicted.

At first glance, making some artificial ice doesn't seem like that big of a deal.

But as Stephen Johnson writes in How We Got to Now, "Our mastery of cold is helping to reorganize settlement patterns all over the planet and bring millions of new babies into the world. Ice seems at first glance like a trivial advance: a luxury item, not a necessity. Yet over the past two centuries its impact has been staggering, when you look at it from the long-zoom perspective: from the transformed landscape of the Great Plains; to the new lives and lifestyles brought into being via frozen embryos; all the way to vast cities blooming in the desert [because of air conditioning and frozen food shipping]."

Who could have seen frozen embryos and vegetables shipped around the world and giant datacenters filled with microprocessors?

This desire today to stop tech before it starts is part of a rising anti-tech paranoia that comes from the power big tech companies have in the modern world. Another pattern of history is that we love to crown heroes and we love to bring them crashing down too. We once lauded tech companies with praise and parades and now we're ready to rip them all down. The rising anti-tech movement on both the right and the left sees tech as the root cause of evil in the modern world.

If you want to point to the dark side of tech it's not all that hard. It's easy to look at social media and point out phone addiction or how badly dialogue and decorum have declined and that must be why we have nasty elections in America and Europe.

Of course, we're forgetting that Hitler, Mao and Stalin didn't need social media to spread messages of hate or to get people whipped up into a frenzy, so maybe social media isn't the whole story. Social media also connects amazing people who would never have met in real life circles. I count some of my closest friends as people I first met online.

Maybe it's like that old Eric Clapton song, "It's in the way that you use it."

If anything, technology is a mirror of us. It's a reflection. It's not outside of us. It's a part of us.

It's both good and bad and everything in between.

But we make it more good by interacting with it, by pushing and pulling it from every side and finding balance. We fix it by playing with it and adapting to it and adapting with it.

When OpenAI put ChatGPT onto the Internet, they immediately faced exploits, hacks, attacks, and social media pundits who gleefully pointed out how stupid it was for making up answers to questions confidently.

But what they all missed is that they were a part of the free, crowdsourced product testing and QA team for ChatGPT.

With every screw up immediately posted on social media, OpenAI was watching and using that feedback to make the model smarter and to build better guardrails around it. They couldn't have done any of that behind closed doors. There's just no way to think up all the ways that a technology can go wrong. Until we put technology out into the real world, we can't make it better. It's through its interaction with people and places and things that we figure it out.

It's also real life feedback that makes tech safer faster.

You can hammer away at your chat bot in private for a decade and never come close to the live feedback that OpenAI got for ChatGPT. That's because people are endlessly creative. They're amazing at getting around rules, finding exploits, and dreaming up ways to bend something to their will. If you put one million of the smartest, best and most creative hackers and thieves in a room, you still wouldn't come up with all the ways that people will figure out to abuse and misuse a system. Even worse, the problems we imagine are not the ones that actually happen usually.

In this story in Fortune, OpenAI said exactly that. “[Their] biggest fear was that people would use GPT-3 to generate political disinformation. But that fear proved unfounded; instead, [their CTO, Mira Murati] says, the most prevalent malicious use was people churning out advertising spam."

Behind closed doors, they focused on imaginary political disinformation and it proved a waste of time. Instead it was just spammers looking to crank out more garbage posts to sell more crap and they couldn't know that beforehand. As Murati said "You cannot build AGI by just staying in the lab. Shipping products, she says, is the only way to discover how people want to use—and misuse—technology."

Not only could they not figure out how the tech might get misused, they didn't even know how people would use the technology positively either. They had no idea people wanted to use it to write programs, until they noticed people coding with it and that only came from real world experience too.

Think about that for a second. One of GPT's top use cases is getting it to write code, or correct code, or document code or write code to do complex tasks with things like AutoGPT. That project rocketed to about 70K Github stars in 3 weeks. It's probably the top use case. Do things and execute code to do it.

And OpenAI didn't see it with earlier versions of GPT, until they put it in the real world and creative, intelligent, craft and wonderful humans figured out what to do with it. That's why we have CoPilot.

You might think that popping Bubble Wrap was something kids figured out after bubble wrap was a hit for shipping stuff around the world. But kids having fun was the original idea behind it! The inventor thought it would make great wallpaper long before it was ever used to keep sensitive equipment and paintings from getting smashed up in shipping.

You know that Nalgene water bottle you take with you in the car or when you go on hikes? It was invented for storage tanks and centrifuges and filters but it didn't really sell all that well until the president noticed some of the scientists had turned it into bottles and taken it camping. They tried it out with some Boy Scouts and it was a hit. The rest is history.

In other words, not only do we not know the things that can go wrong until we put a new technology into reality, we often have no idea what good things they will do with it either!

Of course, the Doomers worry that we can't fix problems in reality, especially when it comes to AI, because it will be all powerful and self-upgrading and murderously homicidal, like a brilliant Chess Master enemy in a thriller movie who knows all the moves you'll make before you make them. If we make something smarter than us, then we won't be able to control it or adapt to it and it will wipe us out! We won't really know what it's thinking and if it's smarter than us it can trick us and manipulate us because we're helpless and stupid organoids.

(Source: Marvel X-Men New Mutants)

They worry that a single misstep is enough to send us hurtling headlong into the abyss.

So let's take a quick turn into AI doomtown to see if they're right.

Welcome to Jonestown

Dan Shipper wrote a great article on the Doomers. He managed to read everything on Less Wrong and Eliezer Yudowski's book and listened to hours and hours of podcasts.

Better him than me.

I could barely choke down Bostrom's Superintelligence, which was deeply informed by Yudowski and his ideas. I found it mostly absurd, poorly thought out and frankly, just straight up boring. I was shocked that so many folks found it compelling until I remembered that people actually love being afraid and they love imagining the end of the world.

I do occasionally read Less Wrong. It's got some good guest writers from time to time. Less wrong is a fantastic blog name too. It comes from a critical thinking concept and if you know anything about me you know I'm a massive fan of critical thinking. The book Super Thinking sums it up nicely:

"The inverse of being right more is being wrong less. Mental models are a tool set that can help you be wrong less. They are a collection of concepts that help you more effectively navigate our complex world."

The author talks through an example of healthy eating. A direct approach to getting healthy would be to construct a complex healthy diet plan with controlled ingredients. Not a bad approach but it's really complex and hard to maintain consistently over time, which is why folks fail. They come storming out of the gate and lose weight but find that keeping a calorie journal for years on end is tedious and boring and saps the fun out of eating.

The less wrong approach is to simply try avoiding unhealthy options instead.

Let's say you go to a restaurant. You scan the menu and immediately scratch out the burger and fries and the milkshake and the deep fried chicken. You pick the salad. Simple and easy. Maybe it's not a perfect salad because of too much sugary dressing, so you ask for a salad with dressing on the side the next time. You pick the least wrong choice and it's a lot easier to maintain that over time.

But the critical thinking concept and the blog name are all the two have in common most of the time. The core writings of the Less Wrong blog, which come from Yudowski's theories, co-opt the language of logical thinking in the service of a doomsday cult. If you frame yourself as a rational, scientific thinker, that helps disguise muddy, distorted thinking. It's much the same way Scientology uses the language and terminology of scientific thinking in service of something profoundly unscientific.

One of the basic criticisms of the AI doomers is that we don't understand these AI systems and we should prioritize research that helps us understand them. That's true of the open letter too. The letter called for a halt of GPT like systems and a switch to a 100% focus on explainable, controllable AI.

Both arguments center on the idea that we don't understand the systems we're building. They're black boxes. This is true. We scale them up through machine learning's bag of statistical tricks and voila we have intelligence. We don't really fully understand how they work.

But so what?

Reality is a black box.

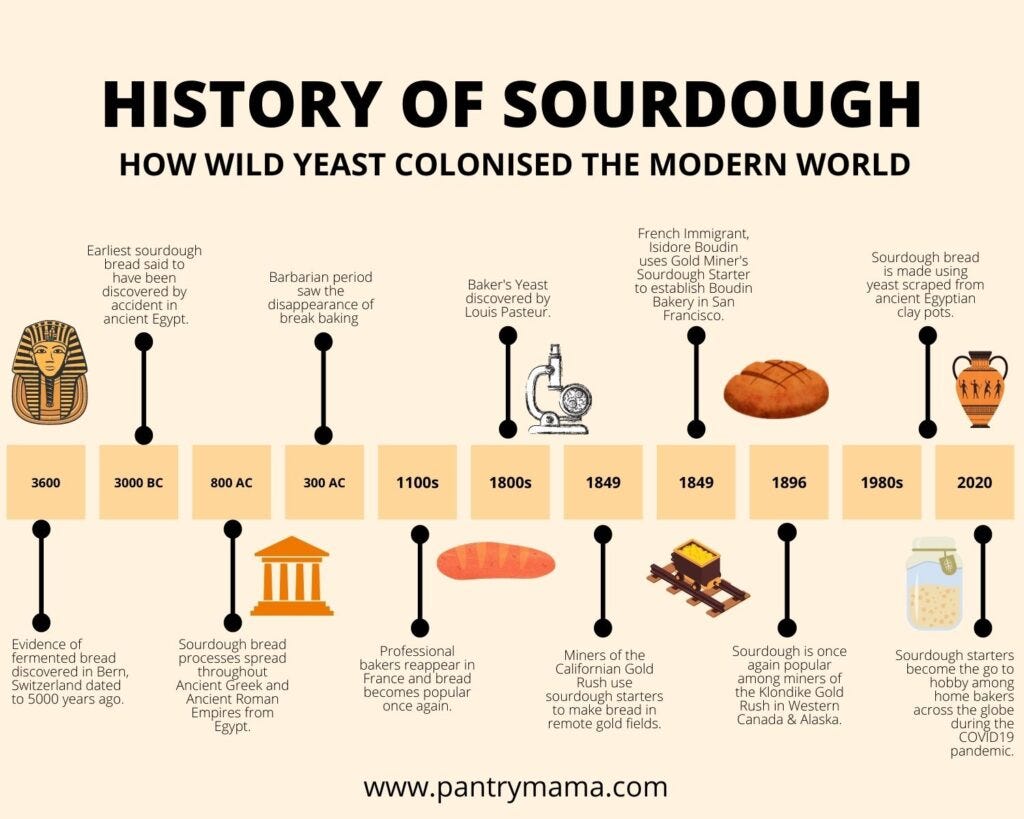

Do you know how a plane flies? Do you understand quarks or gravity at a deep level or why it even exists? What about how to build an engine? What about how to make bread from scratch? Can you build a skyscraper? We use things we don't understand every day.

For millennia people didn't know what made bread rise. They didn't know yeast existed because they didn't have microscopes and couldn't see it. They just knew that places near beer making were good places to make bread or hot places.

And make bread they did, using the magic, invisible, black box technology of yeast.

There are tons of examples of it. You are a probabilistic black box decision maker too. All people are.

There is no guarantee you will do what you're told or that you'll always make the right or best decision no matter how much the nuns spanked you with rulers in school or your parents told you you're special or the Party made you sing patriotic songs. That's because we're a complex system interacting with an infinitely complex system called reality. We don't know how we do what we do. We barely understand anything about our own make up and our minds or how our body works.

People planted crops for thousands of years without knowing that soil was alive. They just knew if you kept planting the same soil again and again or with the same kinds of vegetables, you couldn't plant there anymore. All the microorganisms in the soil died if you did that but they couldn't see those little microscopic organic machines, so they only knew that A leads to B through observation. Keep planting and crops die. So they rotated the soil. They'd leave part of the land "fallow" aka empty, so it could renew its magical ability to grow things. They reverse engineered it.

Observation is the key here. It's the key to working with black box systems.

We look. We observe.

We see that bread tends to rise near beer making. Great. Let's build bread makers near there and see if it still works.

Crops keep failing if we plant them in the same plot of land. Stop doing that.

Observe. Reverse engineer.

We don't need to understand everything about how something works. We can understand how it's affecting things by watching the results and adjusting. We know whether something is working well or not by what it does. We see the outcomes and we make changes. We tweak it until we get closer and closer to something that works more often and breaks down less and we'll do the same for AI. We're already doing it.

People are using Reinforcement Learning and Reinforcement Learning through Human Feedback (RLHF) and Reinforcement Learning through AI Feedback (RLAIF) and guardrails software and more of it is coming. It's not as if the alignment and guardrails concept is totally new and that nobody has heard of it or that there aren't researchers deeply passionate about it working on it in the real world right now. Again, the real world. That's where things get fixed.

Observation of what's actually happening also helps us separate reality from fiction. Whenever there is a delta between reality and what you think, reality is always right. Take something like the predictions of massive AI job loss.

Where is the widespread disruption of jobs?

We've seen study after study that claims that we'll automate away all the jobs. Go ahead and Google "robots take all the jobs" and you'll find so many lazily written stories that you'd be forgiven for thinking they were written by ChatGPT.

We've seen artists in an uproar that they'll be outmoded by Midjourney and Stable Diffusion and they'll be out of work and living on bread lines. It's a great story because it's built on fear and if you want to rally up a lot of people, fear is one of your top tools. Make people afraid and you can lead them by the nose to do anything. Fear is how the Copyright Alliance that artists have stood against for decades, the same folks behind SOPA and PIPA legislation that got smashed down, have now co-opted the artists to sue Stability and Midjourney and Microsoft and OpenAI for a dramatic expansion of copyright.

The end of all jobs is a fantastic sci-fi story too. Stories are about conflict. And what better conflict than the meltdown of an advanced technological race?

I'm not immune myself from writing such a story. I wrote one about robots destroying all the jobs about twenty years ago, called In the Cracks of the Machine. I didn't see self-driving cars coming but I saw it starting with fast food robots.

But what are we actually seeing here in reality?

The exact opposite.

We're seeing new jobs created.

I see new companies spinning up almost daily around generative AI and VCs throwing money at them by the boatloads. We've seen 100M people happily using ChatGPT. I've never seen so many software companies race to add its amazing capabilities to their software.

Maybe you're thinking it's too early to tell. The generative AI revolution is just getting started and the job losses are coming soon and we've got to be ready. Maybe. Time will tell. But as we saw earlier, we've already destroyed all the jobs multiple times and we've always created more jobs. Not just more jobs, but more varied jobs too.

It wasn't long ago that everyone's job was "get food" or "grow food" and now only 3% of us are in agriculture while the rest of us are happily writing articles, being lawyers, building cars and trucks and skyscrapers, painting and moving numbers around on spreadsheets. The electric lightbulb killed the whale oil industry but few people are clamoring for a return to killing whales so we can dig the white gunk out of their heads to make candles.

The good news is, we've already seen at least one new job created:

Professional AI scaremonger.

But the Doomer arguments go further. They say this time is different. AI is different. It will break the eternal pattern. If we make something smarter than us, maybe we can't fix it? Maybe we can't reverse engineer it or get it to do what we want? It could get out of control fast and then we're done for, because it's a lot smarter than us and we're going to be too stupid to see it.

This misses the kinds of parallel technological upgrades that might develop alongside AI that change the game like a breakthrough in alignment or just better explainability that we're already pouring billions of dollars into with research institutes accelerators like DARPA and companies that have a strict culture of safety in AI like Anthropic. It also leaves out the fact that we will have lots of AIs and many focused on alignment and watching other AIs themselfs. It leaves out fantastical new tech possibilities like brain implants and human intelligence augments. Those are just the fantastical ones. We're already developing tools to see how training affects the "minds" of LLMs and we'll develop new techniques to peel back the block box and get a better sense of what's happening there, like Eleuther AI's Transfomer Lens.

Shipper's summary of the basic Doomer arguments against AI go like this:

"If, through trial and error, you’ve built an AI that thinks you find:

It’s hard to know if you’ve successfully aligned it because they “think” so differently than us

They are not guaranteed to be nice

Even it doesn’t explicitly intend to harm humans it could kill us all as a side effect of pursuing whatever goal it does have "

Bostrom's book tries to give some examples of how this can all play out in a bad way. Here's a few:

"Riemann hypothesis catastrophe. An AI, given the final goal of evaluating the Riemann hypothesis, pursues this goal by transforming the Solar System into “computronium” (physical resources arranged in a way that is optimized for computation)—including the atoms in the bodies of whomever once cared about the answer.

Paperclip AI. An AI, designed to manage production in a factory, is given the final goal of maximizing the manufacture of paper clips, and proceeds by converting first the Earth and then increasingly large chunks of the observable universe into paper clips."

What's mind blowing about these examples is not the potential existential threat of superintelligence, but the sheer number of lazy, idiotic assumptions in them.

To start with, these aren't examples of superintelligences, aka strong AI. They're examples of weak AI writ large. Weak AI is any small, narrow AI that's hyper focused on one thing. It has no goals of its own, no agency, no capability of doing anything else, no ability to look at its plan and modify that plan. If it's an AI focused on classifying what's in images, it can't learn to also write poetry too. It does one thing and one thing only.

Bostrom here imagines that a superintelligence, able to outperform humans on any task or idea, would spend its time on something simple like paper clip maximization. The very idea that a superintelligence would become obsessed with such a trivial goal as solving pie or making paper clips out of everyone makes very little sense. It sounds more like a small 20 line Python script gone haywire than a super smart entity.

Let's really try to actually imagine a superintelligent digital mind. It would be something that's able to surpass human thought on almost any kind of task or topic or goal. What would it be like? Well, we're already seeing complex, emergent behavior in our large language models (LLMs) today. This fantastic graphic from Google shows the kinds of emergent capabilities that spontaneously show up in LLMs as we scale their compute and training data.

In other words, as we scale up a relatively simple training methodology of deep neural nets, we see more and more advanced and complex characteristics from our digital minds. Isn't it likely that a super advanced mind, possessed of a massive number of emergent capabilities, would likely develop complex motivations and behaviors as well, rather than an obsessive compulsive disorder for paper clip maximization?

While it's true that superintelligences might not share our values (thank God, because we've often been selfish, stupid, arrogant, murderous monsters for much of our history), the idea that it might become hyper-obsessed with a tiny goal is incredibly remote and unrealistic.

It also assumes that the agent would follow its initial programming at all and not modify its goals or change its mind or just do something else more interesting.

Actually, calculating pie or maximizing a paper clip factory is probably the kind of thing it would ignore. If it did decide to do it, it's very likely that it would simply delegate such a trivial task to a smaller, weaker, non-sentient, non-self aware agent or program to take care of, instead of doing it itself.

Or it would just write a 20 line Python script to do it.

There are a ton of other lazy assumptions in the idea too. One of the biggest is that it seems to say that there's only one superintelligence in the world and that it can go crazy completely unchecked and there's absolutely nothing we can do about it. This kind of thinking reminds me of a classic mistake in old sci-fi. The difference between modern sci-fi and old sci-fi is that in today's sci-fi technology proliferates to many people at once, paralleling the real world. Lots of people have a computer or spaceships or access to the matrix. If you have only one person with a cell phone it's not a very interesting story. But that's different from old sci-fi.

In old sci-fi one guy would have a submarine and it would be the only one on Earth. But that's not how technology develops in reality. The idea that we'd have just one superintelligence doesn't make much sense.

We're already seeing a race between different public and private groups to develop smarter machines, so it's likely we'll have a lot of different AIs, with a range of ideas, capabilities and alignments. That means there's likely to be a lot of AIs that spot the paper clip maker gone crazy and say "hey, don't do that" and work to stop it, not to mention people as well.

This kind of thinking about superintelligence is a bit how caterpillars might imagine how butterflies think. They've never been a butterfly and they've never met a butterfly so they imagine what it's like to be one and basically they imagine it wrong.

Much of the thinking seems to equate superintelligence with homicidal mania. It also tends to see human nature and evolution as favoring brutal, nasty intelligences. In the paper Natural Selection Favors AI Over Humans, the summary says it best: "we argue that natural selection operates on systems that compete and vary, and that selfish species typically have an advantage over species that are altruistic to other species."

Huh. You mean like this Gobi fish and shrimp who work together every day?

The shrimp dug their home in the ocean and cleans it out. The shrimp has poor eyesight and the Gobi fish has great eyes and it acts as a guard and protects the shrimp.

The idea that evolution always favors selfish behavior flies in the face of millions of years of evolution.

Ants are tiny by themselves but collectively they build great things. Gorillas gather in groups and stick together to protect them from the wilds, as do many other animals.

Humans are the greatest collaborators in the history of the world. We got to where we are through collaboration.

Gorillas can't collaborate with more than 50 other gorillas and usually they form tribes of 10. Humans on the other hand can find common ground with 100s of millions or even billions of other people that they have absolutely zero in common with otherwise. How else to explain nation-states and people's patriotic fervor for their country? It's just some lines in the sand that our ancestors made up. None of it is real. And yet it feels very very very real and important to us. We're willing to fight and die and work together with all of our fellow countrymen.

Corporations are nothing but hives of people working together. Be honest, how many of your coworkers would you give the time of day to if you didn't work with them? I'm betting even if you're a big extrovert with lots and lots of friends, you wouldn't find common ground with the vast majority of people you work with right now. Most of us have a few friends at work and everyone else is just someone we work with towards a common goal set by someone else.

Collaboration at a massive scale is one of the things that makes humans unique. It's like John Nash discovered, we don't just do the selfish thing, we do what's best for us and the group. We find balance. We work together.

Nature and evolution tend towards balance too. Rabbits don't proliferate until infinity so that there aren't enough wolves to eat them and wolves don't eat all the rabbits so there are none to eat next year. Deserts don't expand over the whole Earth. Seas reach a shore.

“The Best for the Group comes when everyone in the group does what's best for himself and the group," says the character of Nash in the movie, A Beautiful Mind.

The idea that AIs will find no possible reason to collaborate with us and no reason to combine forces makes zero sense and doesn't track with anything in evolutionary history.

Thinking About Thinking Machines

In the end, how you think about intelligent machines says a lot more about you than it does about AI.

It's a Rorschach test.

People see what they want to see in AI.

If you're a person who spends all their time obsessing about the end of the world, you'll see that in AI too. If you spend all your time thinking about injustice and what can go wrong, you'll tend to see what can go wrong.

I'm an engineer and a creative writer. I love the possibilities of creating new things and when I see creativity I see the very essence of life itself. New ideas. New technology. As an engineer I'm great at imagining what can go wrong and finding ways to fix it. That's what engineers do.

It's also what engineers are doing right now with AI.

They're dealing with its problems as they happen.

People are prompt injecting ChatGPT and people are already coming up with solutions to stop it. That's the push-pull pattern of history. Problems lead to solutions again and again.

We're already aligning AI with our goals and OpenAI is one of the teams leading the way. OpenAI red teamed GPT-4 so that it's already much much more aligned that earlier LLMs. Expect that trend to continue. We don't need a pause. We need to build these systems and study them in depth so we can find ways to make them better. We can't imagine what they're like. We have to dissect the frog to know what's inside. That's how science works.

It's also likely that we're just around the corner from a breakthrough in our understanding of models with so many engineers and researchers working on it. That will dramatically accelerate our ability to align them.

But what if this time is different? What if the pattern of millions of years of technological integration is broken? What if we're horses and AI are cars? What if we're doomed to decline as intelligent machines take over the planet and lead to a future that doesn't include us or includes us less and less?

Here's where I admit that I don't spend much time worrying about the end of the world. If I'm a Trilobite, it's not my job to worry about the world of dinosaurs. If superintelligent machines gradually outmode us, like Homo Sapiens outmoding Cro-Magnon man, then so be it. If China invades Taiwan tomorrow and starts World War III and the nuclear bombs start falling what are you and I going to do about that? If a meteor streaked from space tomorrow there would be absolutely nothing we can do about it.

There are a million ways for the human race to go extinct that are a hell of a lot more probable than superintelligent machines going Terminator. Nothing lasts forever and frankly we've only been around a very, very short time when it comes to the dominant species on the planet anyway. We've been around just under 2 million years and the Trilobites ruled for 300 million. We've probably got a ways to go by that estimate.

The stronger likelihood is that we just evolve with the machines, with upgraded wetware and nano in our brains to make us superintelligent too but I don’t want to stray too far into sci-fi land. We like to think that we have strong control over the future or chaos but it’s an illusion.

And if we're around 300 million years from now, it's likely that the new version of us that exists will be one that co-evolved and integrated with superintelligent machines. They're much more likely to be one of the main reasons we stick around that long than the reason we go up in flames.

Because really, what doesn't benefit from more intelligence?

Is anyone sitting around thinking I wish my supply chain was dumber? I wish cancer was harder to defeat. I wish drugs were harder to discover and materials were harder to create. I wish economics were more challenging to study and that we made worse decisions with less data.

Nobody.

Intelligence will weave its way into every single aspect of our lives, making our economy strong and faster, our lives longer and our systems more resilient and adaptable.

It will be an age of ambient intelligence.

Of course, something will be the end of us eventually.

Something we can't see or predict.

I don't worry too much about the end of the world and I don't recommend you spend much time on it either when there are plenty of more pressing problems to worry about now.

I'm an engineer. I take problems as they come and I do what engineers do best. I fix them. And I trust we'll keep doing that with AI and every other technology we invent or co-invent with our intelligent machine friends in the future. I believe there's a solution to every problem. A real solution, not a magical solution like let's shut it all down and stop all progress, which is absurd, unrealistic, and impossible.

If you choose to listen to people who have a problem for every solution instead, then you might as well get your bunker and bug out bag ready.

But while you're down there in the silo, with no windows and no light, I'll be up here, having a beer and a bite to eat with the people I love and bathing in the sun streaming in through the windows. At least if the end comes I won't have already lived it a million times before it happened and magnified my suffering.

As Robert Frost once wrote: "Some say the world will end in fire and some say in ice."

But I say when it comes to destruction, ice is just as nice as fire and will suffice.