(Source: DALLE-2 AI)

Is life getting better or worse?

Will the future be better than today?

Two seemingly unrelated things got my wife and I talking about these big questions over Saturday breakfast: Stranger Things 4 and whether we should have children.

The choice of whether we should have kids is pretty obviously related to those big life questions. Every potential parent wants to know if they're bringing their kid into a better world, one with a bright future.

With constant bad news running on the 24x7 news cycle and social media magnifying everything it's easy to feel like the world is getting a lot worse by the minute. Two years of COVID and lockdowns. The Jan 6 Insurrection. The quick collapse of Afghanistan into the hands of the Taliban after a twenty year war. War in the Ukraine with threats of a nuclear WWIII. Rampant inflation. School shootings. Cancel culture. Wokeism. Culture wars.

It feels a bit like that old Billy Joel song: "We didn't start the fire. It was always burning, since the world's been turning."

But you're probably wondering why Stranger Things 4 had us asking that question too?

It started because we were discussing the wild 1980s nostalgia in that show. The plot is really a mashup of all things 80s, from Nightmare on Elm street movies (with Robert Englund who played Freddy Kruger even making a cameo as Victor Creel), Stephen King novels (with the font of the series intentionally taking inspiration from those book covers), the Firestarter movie and the bleeding nose of the father with telekinetic powers, Marvel plots of superpowered kids and evil scientist experiments, the Goonies, Dungeons and Dragons and the Satanic panic by religious conservatives.

I said to my wife, "In 10 years someone will make a plot with all the things Millennials loved."

She said, "I don't think so because the 80s was different. It was a golden, pre-internet time where anything seemed possible and people thought life would always get better. Who's going to write about 9/11 and the economic crisis and debt with a nostalgic twist?"

She's right, of course, as she so often is when it comes to things I miss.

The 80s do feel different now, the end of an era and the beginning of a new one, a time that will never come again in today's highly connected world.

The show is also a real love letter to all the things that made growing up in the 1980s feel magical. In the western world everyone felt like their life would be better and richer than their parents. It was the beginning of consumer electronics technology that pointed to a bright and bold new future, Walkmans, computers, home video, walkie-talkies, fantasy games. But all that technology was disconnected and it didn't have the dystopian two way mirror undercurrent of the surveillance economy we have today.

The Walkman was just a way to listen to music on the go. Reliving that wonderful, disconnected portable music era has us all listening to Kate Bush's Running Up That Hill and catapulting it back into the top 10.

Nobody had a cell phone to record every little thing that happened so childhood spats and bullying rarely escalated to something that brought in parents and school admins while today the slightest incident makes the news and sparks a nationwide debate. Mostly back then you just had to worry about a few fist fights and maybe a broken bone, not the horror of active shooters with an AR.

Social media didn't exist so we didn't know how much better or worse we were doing than everyone else. Maybe we weren't popular at school and that hurt when we didn't get invited to parties. Now kids can go on the net and see millions of people having fun at any time and feel truly left out. We didn't know if we were ugly either. We could compare ourselves to other kids in our school and maybe some unattainable media models and not feel popular or pretty but now we seem to know exactly where we fit on the hot or not probability curve because billions of people post pictures constantly. There's always a way to feel bad about yourself with someone looking better or having more fun than you at any given moment in time.

All of that retro feeling about a bygone era and a better time has catapulted Stranger Things into success but is it really true or just a feeling we have now that a long time has passed?

There were lots of things we tend to forget about the 80s like the stock market crash on Black Monday, one of the worst recessions since WWII, the farming crisis, Russians in Afghanistan, the height of the Cold War and more.

But is the world getting better or worse today?

If so, how would we know? How would we judge it?

There's no simple answer but let's look at the problem from a few different angles and see what we discover.

From Running Around in the Forest for Two Million Years to the Information Age

Let's start with quality of life.

It's easy to think of human history as one smoothly interconnected upwards thrust of progress and if you zoom out enough, in many ways that's what it looks like.

We went from running around in the forest for 2 million years, hunting and gathering, to a series of major technological revolutions over the last 12,000 years with those new technologies coming quickly over the last 500 years and even faster over the last 100.

For the vast majority of human history though, we were hunting and gathering. The farming revolution is only 12,000 years old. The scientific revolution is a mere 400 years old. The agricultural revolution is 300 years old. The industrial revolution is 200 years old and the information age is only about 50 years old.

There's a feeling that the hunter gatherer era was a brutal and bleak existence, where we all lived hand to mouth, barely getting by, with famine just around the corner at any moment.

There's just one problem. It's not true.

We don't know exactly why humans switched from hunting and gathering to farming. It's likely that multiple tribes migrated to fertile river regions and found a lot of natural abundance and therefore a lot less reason to stop moving around so much, which gradually led us to settle down over time.

But one thing is known:

When we compare farming and hunter-gathering, quality of life took a significant turn for the worse in the farming era.

Anthropologists who spent time studying hunter-gatherer tribes that persisted into the modern era, like the !Kung in the Kalahari area in southern Africa and the Hadza nomads of Tanzania found that they spend roughly 12-19 hours a week collecting food. That leaves the rest of their time free for socializing, leisure, games and fun. In essence, it means hunter-gatherers had a two day work week with a five day weekend, while farmers were working around the clock.

Farming is more productive in the amount of food per area it produces but less productive in terms of the amount of food per hour of work. In other words, farming is really hard.

Fast forward to today, with hustle culture and billionaire future-makers like Elon Musk working 80-90 hour weeks and the rest of us barely taking two week vacations and by all measures it seems life has gotten worse since those days in the forest. Instead of hanging out with our family and making love and playing games and singing we're working endlessly.

Even worse, hunter-gatherers were healthier too. As Tom Standage writes in The Edible History of Humanity, farmers suffered a much wider range of diseases, and had less varied nutrition and were shorter as a result. The difference was what they were eating. Hunter-gatherers ate a wide range of plants, taking about 75% of their calories from those plants while famers were eating the same things over and over and over. Wheat and rice are more reliable calories but they don't have a complete range of nutrients as a varied diet of plants. Looking back at the archeological remains tells the tale.

Writes Standage:

"Skeletal evidence from Greece and Turkey suggests that at the end of the last ice age, around 14,000 years ago, the average height of hunter-gatherers was five feet nine inches for men and five feet five inches for women. By 3000 B.C., after the adoption of farming, these averages had fallen to five feet three inches for men and five feet for women. It is only in modern times that humans have regained the stature of ancient hunter-gatherers, and only in the richest parts of the world. Modern Greeks and Turks are still shorter than their Stone Age ancestors."

So it looks like we traded a two day work week, a lower rate of disease, and more nutritional value in the hunter-gatherer era for a 5-7 day work week, more diseases and worse nutrition, meaning quality of life declined by many of our most popular metrics.

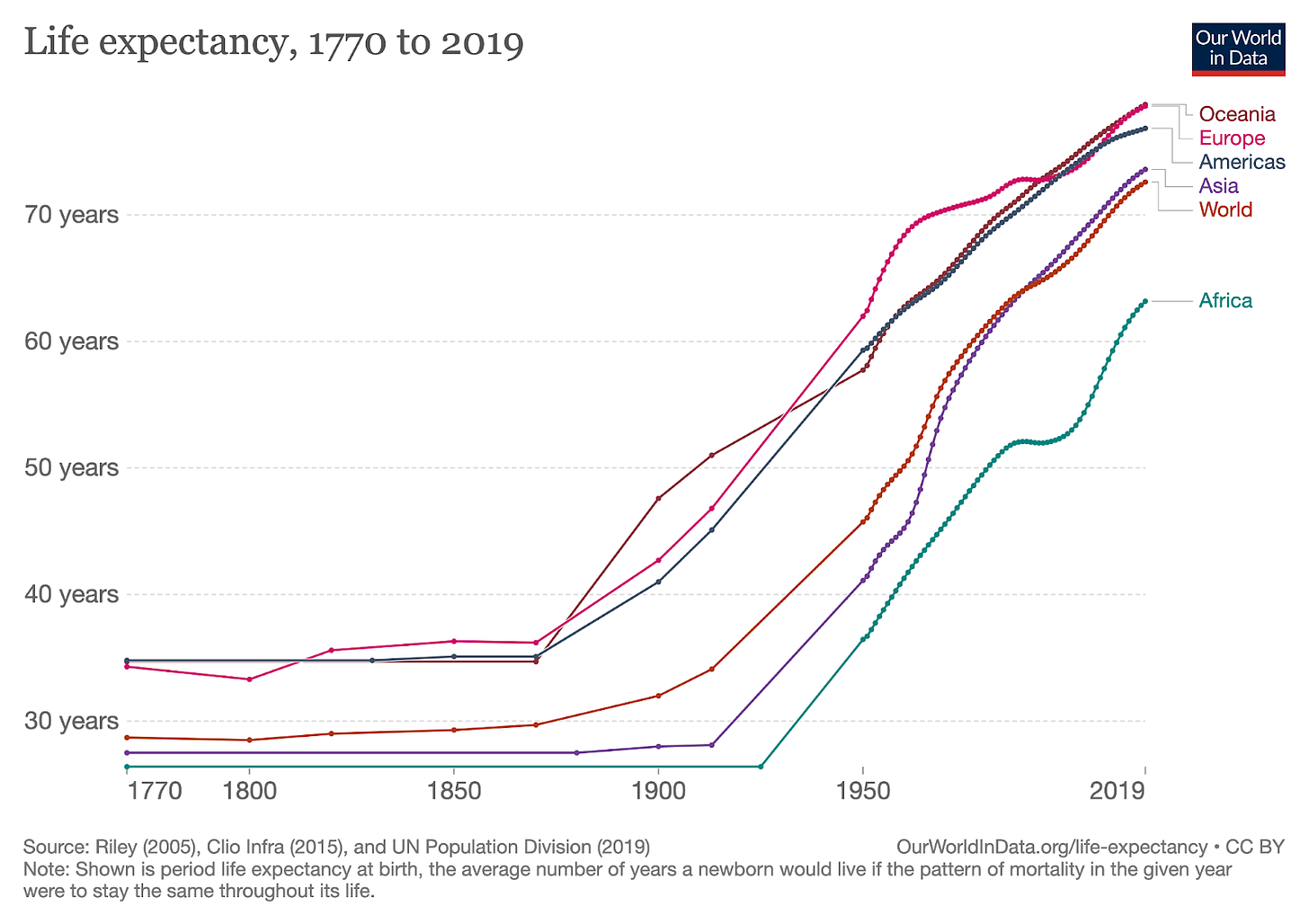

So how about another metric, longevity?

Surely we were living longer than our forest dwelling kin of the past?

Unfortunately, right up until the 1850s, we had about the same life expectancy as our ancestors. People across the world, whether they were living in the technologically advanced west, in the Americas, in China, Africa or India, it really didn't matter. It also didn't matter if you were rich or poor, believe it or not. Average life expectancy was about 35 years.

Of course, some people lived into their 70s and 80s for most of human history. The problem wasn't our age potential, it was the fact that a lot of people never made it past their childhood. Life expectancy is calculated on averages of how long everyone lived. Today we tend to think of children as health paragons who bounce back from everything quickly but history tells a much different story. Half of all children never made it to adulthood. The actual number is 46.2% but it's roughly half. Think about that for a moment. Half. That means that one of the worst experiences any parent can go through, the loss of a child, was a completely common fact for most of human history. People expected to lose children.

But starting in the late 1800s and early 1900s something changed dramatically and it's been changing ever since.

And that's where our story starts to get very interesting.

Today, the global infant mortality rate is 2.9% and youth mortality rate is 4.6%. Infant mortality is children that die in their first year and youth mortality is people who never reach adulthood. Those stats include every country on Earth, from technologically advanced countries to the third world. What's even more interesting is how precipitously it falls from the 1850s down to today after remaining virtually unchanged for most of human history, a smooth flat line of people dying.

(Source: Our World in Data)

So now we have our first indicator that life is getting better than life in ancient times. We can expect to live past our childhood with average life expectancy about 77-79 years the world over. That means that over the last 122 years most people can expect to get an extra 44 years of life. That's 385,704 more hours on average.

(Source: Our World in Data)

The reasons for that explosive growth in life expectancy point to one of the other reasons that life is potentially a lot better now than it was for the vast majority of history. Medicine is significantly better today than at any time in history and it just keeps getting better.

Medicine, Technology, Manufacturing and Logistics

But the strangest thing about medicine is that it only recently got better.

For most of human history, medicine was a total disaster. Even though the average life span was getting longer, it wasn't because of medicine. Going to a doctor was often worse than doing nothing at all. It's strange that we had incredible buildings, tremendous art, big cities, boats that could carry spices from near and far, and steam engines but our medicine was still atrocious.

As Steven Johnson writes in Extra Life: A Short History of Living Longer, "If you were unlucky enough to come down with the flu, or be born with a hereditary disorder that caused porphyria, you were better off avoiding doctors altogether and letting your body’s immune system work to heal you rather than seeking out the phony cures of arsenic or leeches."

If you look closely at that life expectancy chart, you can see a dip in Europe in the 1800s. That's attributable to a number of disparate factors but one of them was that medicine was terrible pseudoscience that killed more people than it helped. If you were rich in Britain in the 1800s you had access to doctors and at one point that made rich people even more likely to die than their poorer brethren who didn't have access to doctors.

Doctors didn't even know to wash their hands. In the 1800s they regularly dissected corpses and then treated pregnant women and the sick and dying without any idea that they were transferring microorganisms and making things much much worse. Even worse it was another 50 years before the practice really took off, with the discovery of germ theory.

Johnson goes on to detail the horrific last days of George Washington to showcase the typically terrible treatments of the time. Washington was bled multiple times removing as much as 60% of his total blood supply. Doctors coated his neck with a paste made from wax and beef fat mixed with dried beetles, an irritant that created horrible blisters that they then opened and drained. They had him gargle molasses, vinegar and butter and then gave him an enema and a purgative.

It may surprise you, but none of these interventions helped in the least.

Today anti-vaxxers debate the efficacy of mRNA vaccines on social media but few people worry about going to the doctor when they have stomach pains or a broken wrist or they break out in hives. That wasn't the case for most of history where sepsis and cross-contamination were common and most medicine was utterly useless.

Even as life expectancy started to rise, medicine lagged badly. In the 1900s most of the medicines at the pharmacy were nothing but quack science, laced with arsenic and heavy metals and worse. Coca Cola started off as a patent medicine, a kind of "medicine" where the makers didn't have to bother telling you what was in it. It was only later, when the head of the company saw the winds were moving against patent medicines that he changed course to making it a refreshing drink. Ironically, they kept the cocaine in, with many of the raging teetotalers who got alcohol banned in the 20s going to the pharmacy to enjoy a refreshing pick me up of coke. As noted in Wikipedia, "Coca-Cola once contained an estimated nine milligrams of cocaine per glass."

Medicine for the vast majority of human history was based on no data and no real science. The dominant theory of disease up until the late 1800s was miasma theory, the idea that the Black Death, Cholera, Chlamydia (which probably made it easy for husbands to get away with a trip to the brothel because they could blame venereal disease on an ill wind that got them sick on the way home from work instead of a roll in the hay with a hooker) and other diseases spread through noxious air clouds. Most of the torture inflicted on Washington and God knows how many others over the years was designed to get something out of the body when we had no idea where that bad stuff actually lived inside of us because we didn't have microscopes that could see those invisible little monsters or the data collection necessary to discover patterns in disease distribution.

The big breakthroughs started to come in four ways.

The first was better data collection and the application of a little studied aspect of mathematics, probability, which was primarily used to study games of chance before that.

By the time John Snow traced a Cholera outbreak to a water pump in London and proved it with the help of a statistician and a local pastor who helped collect data on the outbreak, things were starting to seriously change. Snow and the folks around him still couldn't see the Cholera bacteria, because microscopes hadn't gotten good enough yet, but they could now trace its spread from an origin point and prove beyond a doubt that it wasn't spreading through noxious air but through the water.

That led to further breakthroughs and takes us to the second way things changed, better large scale logistics in cities.

People once debated if a city of a million people was even possible without rampant disease. Because of Snow's work, the city of London finally understood that we probably shouldn't be dumping our shit into the same water we drink. It led to the creation of the famous London sewer system. It was largely operational within only six years and it separated waste from drinking water. Other cities followed in waves until it became standard practice, saving millions upon millions of lives.

More large-scale city level logistics breakthroughs followed, like chlorinated water that killed off a myriad of bugs, pioneered by a doctor named Leal in New Jersey who secretly built a chlorination system with an engineer into the public water works. He survived a criminal trial for doing it but was subsequently vindicated by his efforts as water works around the world soon followed. He went on trial because chlorine is fatal in high doses and people couldn't imagine that a small amount would only kill bugs and have negligible effects on humans.

The third way things changed was superior technology like microscopes.

Better and better microscopes opened up the world of the invisible and put the miasma theory to rest forever. John Snow couldn't see the Cholera that his landmark detective work traced but thirty years later Robert Koch could see it. He also identified the bacteria for tuberculosis. In 1900 the worst killers in the world were influenza, tuberculosis, and gastroenteritis but now that we could see those invisible enemies we could kill them off and fight them more effectively.

It wasn't just medicine either. We had Edison and the first industrial invention think tank make rapid improvements on the light bulb and electricity generation in the race to electrify the world. Contrary to popular belief Edison didn't invent the light bulb but he did make the light bulb long lasting, with a bamboo filament that took light bulbs from a few hours of use to six months of use, along with numerous other improvements in dynamo electricity generation and how to insulate wires from rain and snow and much more. Technology started to overlap, enhance and reinforce developments in other fields faster and faster.

Things started to speed up much more rapidly after that from 1900-1960s. A series of technological inventions and discoveries came together to bring us strong medicine that forms an invisible shield around us that few people today perceive or think about but that's always protecting us.

Antibiotics killed more of the microbes we could now spot in our stronger microscopes. It's hard to underestimate just how powerful antibiotics were as a technology. We now had drugs that could actually cure people and, even better, they could cure a wide variety of infectious diseases. We take antibiotics for granted now it’s shocking to realize they haven’t been around all that long. The first industrial scale production of penicillin happened at the end of WWII. Allied soldiers landing on the beach at Normandy carried penicillin along with their rifles. Antibiotics let us do things like surgery without killing people with random infections.

After antibiotics we got breakthroughs like randomized double blind placebo control studies that gave us a way to test the efficacy of medicine. Before that we really had no way to know whether a drug was actually making a difference and we had no way to prove it. Double blind control trials led us to the fourth way that things changed for the better:

Regulatory agencies got stronger with more oversight.

You might not think that matters in today's political climate but it matters a lot if you go back in time to see the kinds of problems those agencies were created to solve and when you begin to understand that they actually solved them. Today we tend to think every government body is totally incompetent, the equivalent of the Department of Motor Vehicles (DMV). But if you lived in the 1930s or the 1960s you'd probably see things a bit differently. Two tragedies led to the change.

Teddy Roosevelt had passed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906 but it didn't have much teeth. It did lead to the creation of what would become the FDA but drug companies could still bring any "medicine" to market as long as it wasn't adulterated or "impure" because of additives.

By the 1930s, muckraking journalists, consumer protection orgs, and federal regulators pushed for stronger regulatory authority but even after a series of tragedies, including radioactive beverages and mascara that caused blindness to name a few, they couldn't make much progress. Then in 1937, the Bayer company started making a precursor to antibiotics called Sulfonamide and a company in the States called the S.E. Massengil Company rushed a copy to market that was flavored to taste like strawberries, marketing it as a flavored elixir. It proved deadly and promptly killed over a 100 kids.

At the trial, the head of Agriculture, who was responsible for oversight of drugs, testified that the FDA had done its job because it confirmed that the strawberries tasted like strawberries and weren't "adulterated." They weren't actually responsible for seeing if the formulation could actually kill anyone.

After that FDR signed the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1937 that finally gave the power of testing whether medicines were deadly to the FDA.

But it still wasn't enough. The FDA didn't have to actually test whether the drug worked and anyone could bring any drug to market as long as they could prove it didn't kill you.

That changed in the 1960s when a scientist who just started at the FDA, Dr. Frances Oldham Kelsey, noticed some problems with tests of a new drug called Thalidomide that was popular in Europe at the time. She started investigating a report that it did nerve damage and followed a hunch that it might affect pregnancies. Soon reports of deformed babies were coming fast and furious and she had successfully prevented it from hitting the US market. That led to the second wave of reforms in the 1960s that set it so drug companies actually had to prove the efficacy of drugs with double blind control studies, not just whether a drug could kill you. Now companies had to prove a drug actually worked.

Today we like to think that the market always does what's best but it's just not true. The market often does what's best but sometimes it simply does what's most profitable and at the turn of the century it gave people fake garbage medicine that didn’t cure anything.

It's hard to imagine now how bad medicine was now that medicine is so good. To understand why you just have to look at outbreaks.

The Spanish Flu killed more people than World War I in a span of two years, with estimates ranging from up to 50 million and as high as 100 million people, making it the deadliest outbreak since the Bubonic Plague. The disease was no more contagious than other flus but poor nutrition, mass overcrowding in hospitals, no vaccines, terrible hygiene, and a dozen other secondary factors killed people in droves.

There were no antiviral drugs, no antibiotics, and so doctors treated people with the usual quack medicine that had no effect at best and made it worse more often than not. Treatments included aspirin, arsenic, strychnine, Epsom salts and castor oil. They also made use of bloodletting and other absurd practices that just made patients weaker.

Or take a look at smallpox, one of the deadly killers in the history of the world.

According to Wikipedia:

"In 18th-century Europe, it is estimated that 400,000 people died from the disease per year, and that one-third of all cases of blindness were due to smallpox. Smallpox is estimated to have killed up to 300 million people in the 20th century and around 500 million people in the last 100 years of its existence."

When doctors set out to destroy Smallpox in the 1950s they had some advantages over the virus. Doctors had better data collection to track outbreaks, better regulatory bodies with international reach, like the WHO that was able to coordinate responses in almost a 100 different countries, and a vaccine that could be manufactured in large numbers.

But there were still some major shortcomings. We didn't have the ability to manufacture enough doses for the entire planet, so doctors had to employ a ring vaccination approach. They'd hear of a report of an outbreak and send a team to vaccinate everyone in a circular radius around them. They battled everything from ongoing famines, to complete lack of infrastructure in the third world, to civil war and strife and more to kill off smallpox. They won. The last naturally occurring case of the deadly Variola major was detected in October 1975 in a three-year-old Bangladeshi girl, Rahima Banu.

Fast forward to today. The teams battling COVID 19 had some significant advantages versus the doctors battling smallpox. Infrastructure and technology had reached a tipping point, along with mass communications. The virus' DNA was synthesized within a few weeks of its wider emergence. Drug companies managed to design, test and manufacture a vaccine in under a year, an unheard of speed up, where vaccines typically took a decade or more. A year after that they'd manufactured enough to inoculate the entire Earth multiple times over.

They also had the ability to ship those vaccines that needed to stay super cold all around the world due to better cold storage that's been increasing since the invention of the electric refrigerator in 1918. That would have been impossible during the battle against smallpox, when the only vaccines that could work then had to be able to exist at room temperature and not die out.

The delta between now and then is striking. We were able to manufacture enough vaccines for everyone on Earth and ship it globally. We had multiple vaccines in under a year. We could ship super cold storage vaccines all over the planet with ease.

As of June 2022, reported deaths totaled 6.92 million for one of the most highly transmissible diseases in history. Real deaths are expected to be higher at around 10 million but its still low as on overall percentage of the world population which now tops 7 billion versus the Spanish Flue which killed as much as 5% of the population of the entire Earth. COVID mortality would have been even lower if not for widespread resistance to masks and a rampant and virulent anti-vaxx movement. To put Omicron in perspective, take measles, one of the most infectious diseases in the world. Measles might infect 15 people in 12 days. Omicron can infect 216 people the same 12 day span.

But there’s something incredibly interesting about COVID that you don’t see in the stats.

We reached such an advanced point in history, where people have gotten so used to living out their full and natural lives from childhood to adulthood, where medicines and hospital visits are safe, where we can and do understand the mechanisms of disease transmission, where our water is safe to drink from cholera and deadly historical killers like smallpox are regulated to the history books, where vaccines are designed and manufactured to scale in a few years, that we have the option of refusing vaccines and thinking we'll be just fine.

That's probably because most of us will be just fine.

People today can ignore health restrictions and go to concerts and giant events and not wear masks while bitching about it on social media and still live to fight another day usually.

Sure some folks die but not nearly as many as would have died versus literally any other point in history. Today an invisible shield, built on a stack of medical advances, technological innovation, regulatory interventions, as well as manufacturing and logistics breakthroughs make for a very different world where we can blatantly disregard good sense and expert opinion and the vast majority of people still don’t face any serious consequences for it.

The World of Today, Tomorrow and Yesterday

If you look around you today, you live in a world of magic.

You have medicine that protects you with an invisible shield. Cars used to kill people in even the smallest crash in the 1950s until seat belt technology and a hundred other safety inventions started making cars safer and safer. Now you have a good chance of living even when you crash at 70 miles per hour. Antibiotics kill off tiny invisible invaders in your body. Today's most cutting edge vaccines turn viruses against themselves using the same biotech that viruses are made of, mRNA, to teach your body to defend itself.

But it's not just medicine. We take it for granted when we flip on a light switch and it lights the whole house and doesn't burn it down, a product of the rapid electrification of the world in the late 1800s and early 1900s. We turn on air conditioning to stay cool and store food in a refrigerator to keep it well past its normal decomposition timeline. In our pockets we carry mini-super computers that can call just about anyone on Earth or message them instantly or buy things and have them dropped right at our door in a day. During the pandemic many folks were able to work from home, something impossible even a few decades ago because technologies like Zoom didn't exist. We have batteries so small and powerful that they can keep our Kindle running for a month with no charge and that Kindle feels light as a real book and is just as easy on the eyes.

In late 1968 the Population Bomb book incited a world wide fear that we couldn't feed all the people on the planet and it was right at the time. Famine was all too common. “The battle to feed all of humanity is over," the book promised. In the 1970s, “hundreds of millions of people are going to starve to death.” The book figured we'd just have to let whole swaths of people die in India and China to save the planet.

It didn't happen because of the Green Revolution, a race to make high yield wheat and rice and corn that worked. Now famine is only a reality for 1% of the population at any given time.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

People flocked to Edison's laboratory in the cold and icy winter, getting off the train just to see the incandescent bulbs lighting up the darkness. The famous French actress and beauty Sarah Bernhardt, La Sarah Divine, gave a performance in New York City and made a special trip to see Edison at 2 in the morning because it was like stepping into another world of fantasy where lights came on whenever you wanted them and you could record your voice and hear it played back to you.

We live in that world now and never think about it all.

We just flip on a light and it comes on.

In the past people might hear professional music only a few times in their life, if ever. They might hear a local guitar player or a traveling minstrel or someone might sing at a wedding but now we can turn on Spotify and listen to the greatest professional musicians from all over the world, as well as recordings going back 100 years. We can listen to the sultry sounds of Etta James while cleaning our house, plugged into wireless headphones that blot out the rest of the world with noise cancellation.

None of this means we don't have real problems right now.

We have kids in the States coming out of school with 200 or 300 or 400,000 in debt, something they may never dig their way out of in their lifetime. We have inflation running wild. My sister works as a teacher and has to have a part time job just to cover expenses and too many people can’t make ends meet. A huge number of people live paycheck to paycheck. People are mad and they're worried and bad things tend to happen when you combine declining economics and rage. The invasion in the Ukraine is threatening to spill over into the rest of the world and putting real pressure on food security once more because the Ukraine is so important to food production.

We've gone from the 1980s where people felt like the world was getting better all the time and people expecting to do better than their parents to a place where people feel they may do worse than their parents.

We certainly haven't caught up to our much maligned hunter-gatherer ancestors who enjoyed a two day work week, even if we’ve blown past their life expectancy.

Money is usually a stable, hidden force in our lives that we don't think about but sometimes it just "goes crazy" as Jacob Goldstein writes in his book Money: The True Story of a Made Up Thing. Right now it's going crazy.

Humans also have a tendency to go into periods of horrible self destruction like we saw in World War I and II and we seem to be doing it again.

Progress is never a straight line. It's a period of peaks and troughs like a stock market chart that has setbacks and down periods, not a straight line upwards and onwards.

But if you zoom out, today's world still looks a lot like magic.

The world is a better, safer, more connected place and we're not shitting into the same rivers we drink from anymore because of the work of 10s of thousands of inventors and creators and engineers over the history of the world, along with 10s of millions people who coaxed those ideas forward and made them real, and 100s of millions who fine tuned and improved those ideas and put them into action at the ground level. These were people who fought for change and won. They envisioned a better world and made it happen. They saw problems and found a way to fix them.

To solve the next wave of problems we're going to need a lot more of that kind of progress. We need folks who can look at the world and see something we can change to make a better tomorrow.

After reflecting on my conversation with my wife I can tell you one thing. If you gave me 1 trillion dollars but told me I had to go back in time, I certainly wouldn't go back further than the 1950s and I’d have to think about it even then. Nothing could send me back to the time before antibiotics and electricity and computers and books that I can read anywhere at any time and enough food to feed the world.

And if you look closely, one thing really stands out the more you study history.

We live in a world now that’s so full of incredible advances that we simply take it as a given.

We're probably the luckiest one percent of one percent of people to ever live.

But we should never take it for granted.