As the World Burns: A Reading List for the Post-Fact Era

A few weeks ago, an unexpected best seller rocketed to the top of the Amazon charts:

A few weeks ago, an unexpected best seller rocketed to the top of the Amazon charts:

Nineteen Eighty-Four.

For days the mega-retailer struggled to keep it on the shelves. Publishers raced to print more copies.

The iconic seventy-year-old novel of authoritarianism and tyranny currently stands at number one in classics and number six overall, which means it’s blasting through 100s of thousands copies a month.

Whether it’s Trump spamming executive orders and causing chaos at airports, Venezuela’s economy going from number one in South America to utter collapse or Russia voting to decriminalizing wife-beating 380–3 (seriously), reality is now threatening to put the Onion out of business.

In an era of information warfare, post-facts and outright lies, Americans are turning to the arts to help make sense of it all.

In times of trouble, books become a light in a dark, a way to understand what’s happening all around us.

As the world burns, you might as well have something good to read.

So, in no particular order, here’s your field guide to the apocalypse, fiction first, followed by non-fiction.

Fiction

Nineteen Eighty-Four, by George Orwell

“The best books…are those that tell you what you know already.”

We might as well start with the obvious. In an era of populist uprisings, we the people have spoken overwhelmingly in favor of Orwell’s classic. Everyone read it in high school, but did you really read it? Long before the sci-fi movie “Arrival” floated the idea of language as a weapon, Orwell outlined exactly how to uses words to destroy objective reality. The Ministry of Peace waged war. The Ministry of Truth spread lies and propaganda. Doublethink forced people to hold two contradictory beliefs at the same time, something humans are surprisingly good at. Doublespeak used words to obliterate facts. This is a book that, in the words of the author, is not meant “to be loved so much as understood.”

Brave New World, by Aldous Huxley

“One believes things because one has been conditioned to believe them.”

If Nineteen Eighty-Four is the first book people reach for to understand alternative facts, then Brave New World should be the second. In many ways it’s more clearly analogous to what we face today. If Nineteen Eighty-Four explored the horrors of a totalitarian regime willing to put its boot on the neck of humanity forever, it was in Brave New World that showed how people could numb themselves to the point where they would march willingly to their own destruction, like lemmings plummeting off a cliff.

Fahrenheit 451, by Ray Bradbury

“It was a pleasure to burn.”

Who can forget the opening lines of this sci-fi masterpiece? Montag is fireman whose job is not to stop fires but to start them. He’s an enthusiastic oppressor, a man who never questions the destruction and ruin he leaves in his wake. His wife, Mildred, spends all day zoned out to her television “family,” who pumps her with lies and distractions in an eerie parallel to modern social media. But when Montag meets a young girl who teaches him about a past he never knew, where people didn’t live in fear, his eyes are opened and he can’t go back to his unquestioning ultranationalism. Can he help save literature and himself before it’s too late?

Catch-22, by Joseph Heller

“Insanity is contagious.”

When someone once told Heller, “You’ve never written anything as good as Catch-22,” he said, “Has anyone?” Few novels capture the utter absurdity of existence better than Catch-22. The title refers to a logical paradox, a double bind where no matter what you choose, you lose. It’s the type of book that speaks better for itself than in summary. “It was miraculous. It was almost no trick at all, he saw, to turn vice into virtue and slander into truth, impotence into abstinence, arrogance into humility, plunder into philanthropy, thievery into honor, blasphemy into wisdom, brutality into patriotism, and sadism into justice. Anybody could do it; it required no brains at all. It merely required no character.”

It Can’t Happen Here, by Sinclair Lewis

“The Senator was vulgar, almost illiterate, a public liar easily detected, and in his ‘ideas’ almost idiotic…Certainly there was nothing exhilarating in the actual words of his speeches, nor anything convincing in his philosophy. His political platforms were only wings of a windmill.”

The classic novel that shows how a populist uprising by a ruthless leader could destroy the very foundations of American democracy. Published as fascism swept through Europe, the novel details the rise of Berzelius “Buzz” Windrip, a demagogue who defeats FDR for the US presidency. By sowing fear and promising drastic economic and social reforms, he promises a return to ultranationalistic patriotism and “traditional” values. After his election, Windrip takes complete control of the government and imposes a plutocratic/totalitarian rule with the help of a brutal paramilitary force.

The Decameron, by Giovanni Boccaccio

“Nothing is so indecent that it cannot be said to another person if the proper words are used to convey it.”

As the Black Death rampages across Europe, ten young Florentines escape the plague-infested city and retreat to the countryside where they spend ten days telling each other stories — “tales of romance, tragedy, comedy, and farce — one hundred in all.” This is hands down one of the greatest short story collections ever. It’s impossible to imagine what it must have been like to experience the plague. This was before modern medicine knew their were invisible bugs that could kill you, that sanitation was necessary or disease could quickly overwhelm. The terrible disease slayed nearly a quarter of the population of the Earth by some accounts. Like Viktor Frankl in Man’s Search for Meaning, the Florentines find purpose in the chaos but unlike Frankl, they find it not in love and truth but in sex and laughter. The hundred tales in this tome are some of the bawdiest, most outrageous and funniest ever written, from sexy nuns to heavy drinking priests and corrupt politicians. As the book jacket says, this work is a “life-affirming balm for trying times.”

Siddhartha, by Herman Hesse

“I have always believed, and I still believe, that whatever good or bad fortune may come our way we can always give it meaning and transform it into something of value.”

This remains my favorite book of all time. No other book has occupied the top slot in the thirty years since I first read it. My copy is dog-eared, highlighted, covered with notes in the margins and falling apart, the binding no longer able to hold it together. I’ve given away more copies than I can remember. They never return to me but that’s not unexpected. (According to Buddhist philosophy, they were never mine anyway and nothing is ever really lost.) This is the ultimate retelling of the life of the Buddha. He goes from one extreme to the other, starving himself in the forest with the ascetics, to a life of pleasure and opulence with a beautiful courtesan. But ultimately he gives it all up for a simpler path, the middle way. Never has that message of a return to basics been more powerful.

Non-Fiction and Philosophy

Man’s Search for Meaning, by Viktor E. Frankl

“For the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers.”

In Tools of the Titans, Tim Ferris noted that this book stands at number one on many top performers’ top ten list, and for good reason. Few people can comprehend the horror of the concentration camp or how to make sense of life after such an ordeal, yet somehow Frankl does just that. My grandfather was with the first troops into Buchenwald, one of the first camps liberated by the Allies in World War II. He and many of the other soldiers couldn’t understand what they were seeing. That’s how the mind protects us from horror. Back then, they had no advanced warning to cushion the blow. Nobody, outside of a small circle of soldiers and officers, knew what was really going on deep in Nazi territory. He grabbed two men so thin that could put them both under his arms with ease, and carried them from the camp, his eyes streaming. Yet, Frankl is a man who endured this unimaginable center of suffering and still found a way to see joy and meaning in life. While Nineteen Eighty-Four and Brave New World are pessimistic in their outlooks, this book is the ultimate symphony of optimism.

The Authoritarian Dynamic, by Karen Stenner

“Authoritarians, almost by definition, favor the subordination of the individual to the demands of the collective.”

This is an obscure book by an assistant professor of politics at Princeton. It posits an unexpected theory: that authoritarianism is a natural response to threats. Democracy is always under threat because it’s unnatural. Tribalism, fear, and hatred of others have been the natural order of humanity for much of its existence. The Founding Fathers saw democracy as the great experiment, but Professor Stenner discovers that many people will never be comfortable in a modern democracy. In every era, in all times, there are people who feel that only “right thinking” people should be allowed to express their opinions. They prize conformity, and want to stamp out offensive ideas. Even worse, the book theorizes that many people hold these opinions secretly. Their unease lies dormant for years until a threat activates them, like an army of Manchurian Candidates.

Amusing Ourselves to Death, by Neil Postman

“Americans no longer talk to each other, they entertain each other. They do not exchange ideas, they exchange images. They do not argue with propositions; they argue with good looks, celebrities and commercials.”

A classic from the Reagan era. It was written in an almost laughably simpler time, 1985, when there was no social media, no cellphones, no Internet. It was a time when my parents sent me out to play and told me to “come home before the street lights come on.” But even back then, Postman saw the rising barrage of news on TV, the jarring juxtapositions, the lack of meaning and context as destructive to our concentration and sanity. Fast forward to 2017 and the near endless supply of pointless media has only accelerated the collapse of our attention spans as we dissolve in endless distraction.

The Smart Girl’s Guide to Privacy, Practical Tips for Staying Safe Online, by Violet Blue

“Social media, online dating, photo sharing, mobile apps, and more can make a modern girl’s social life a dream — or a nightmare.”

Written by a Wired security columnist, this is a guide to protecting your personal identity online. Ostensibly written for women, it applies to nearly everyone today. When everything you say can be used against you, and keywords alert Big Brother to who you are and what you believe, it helps to scrub your online life. It can also serve as an operational guide for online activists. If people want to speak their mind, they should take care that the blowback doesn’t come back to haunt them forever.

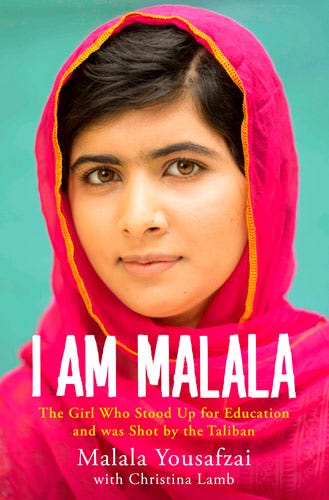

I Am Malala, by Malala Yousafzai

“When the whole world is silent, even one voice becomes powerful.”

It’s safe to say that I’m not braver than this little girl. She gained fame after getting shot in the head by the Taliban in Afghanistan and surviving. If you want to know what it really means to stand up for what you believe in, in the face of great personal danger to yourself and your family, then this is your book. Written by the youngest ever recipient of the Nobel Prize, it stands as a shining light of human triumph in the face of the most horrific and backward hatred.

Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia, by Peter Pomerantsev

“In the new Russia, even dictatorship is a reality show.”

British producer Peter Pomerantsev plunges into modern Russian life and finds a surreal horror show. It’s a dictatorship unlike any ever seen in world history, one far more covert, while still secretly vicious, and exceedingly subtler than the crude authoritarians of the past. While Stalin and Mao needed to control every aspect of life with an iron fist, Russian oligarchs wield power and leverage corruption on a massive scale. This book peals back the iron curtain and shows you what happens when government becomes reality TV.

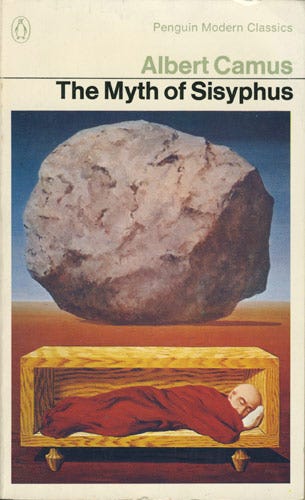

The Myth of Sisyphus, by Albert Camus

“In order to understand the world, one has to turn away from it on occasion.”

This existential masterpiece is an elegiac meditation on finding meaning when it seems we’re nothing but meaningless fragments in an uncaring universe. The title refers to the Greek hero confined to an eternity of rolling a rock up a hill as punishment for his crimes against the Gods. While the situation seems utterly hopeless, Camus finds dignity and courage in the metaphor for our seemingly pointless existence. He imagines Sisyphus taking great pride in rolling his rock and in that moment where the rock rolls back down, he is totally free, able to follow it down completely unburdened, if only for a fleeting moment.

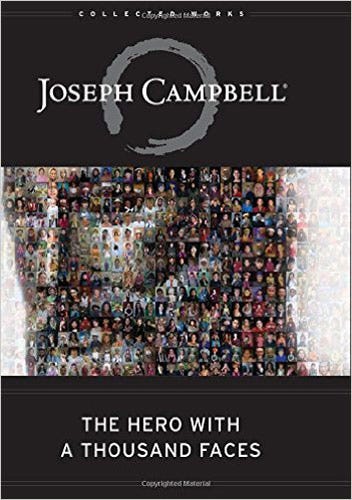

Hero with a Thousand Faces, by Joseph Campbell

“The agony of breaking through personal limitations is the agony of spiritual growth.”

This is one of the greatest works of comparative literature ever written. It inspired countless storytellers and filmmakers, including a young George Lucas as he worked on Star Wars. Campbell virtually invented modern mythology studies. In this classic he uncovers the mysterious singular story of the hero that seems to run through all cultures, in all times. This monomyth exists even in cultures that had no contact with each other, suggesting there is a universal truth that all men and women share. It’s tropes are familiar to us now: the call to adventure, the refusal of the call, the magic boon that gives us the strength to battle against unthinkable odds. But many people misunderstand this book. They don’t realize that the call to adventure is not just a story; it’s the story of each and every one of our lives. The call to adventure is yours. Every generation must stand up for what’s right as the darkness of the gathering storm smothers the land and all truth seems to die.

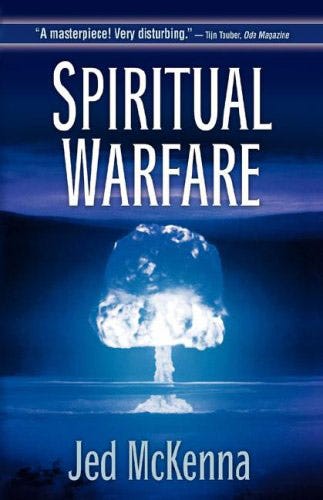

Spiritual Warfare, by Jed McKenna

“We never questioned or doubted. Never stood up. Never drew a line. We never walked up to our parents or our spiritual advisers or our teachers or any of the other formative presences in our early lives and asked one simple, honest, straightforward question, the one question that must be answered before any other question can be asked: ‘What the hell is going on here?’”

I’ve written elsewhere that Jed McKenna’s enlightenment trilogy are the most dangerous books ever written. In some ways I don’t want to recommend them to anyone. Reading them often feels like falling out of a plane. And yet sometimes you need to see the truth in a way that is clear and unforgiving. This third book in the trilogy is the kind of book you find when you have nothing left to believe in and don’t know how to continue. It’s the kind of book you find when you’ve lived through a war, gotten cancer, or lost a child. Warfare spends much of its pages examining the Upanishads, a classic of Indian mythology. In the Upanishads, a great warrior, Arjuna, a leader in a divisive civil war, looks across the field and sees friends and family arrayed against him. He crumbles in a fit of despair, unable to lift his sword to fight against his former loved ones. When Frankl’s heart-centric message no longer moves you and you can’t find pride in rolling your rock like Camus or when Siddhartha’s ability to find value in good and bad fortune eludes you, it’s Spiritual Warfare that will help you find a reason to pick your sword back up and continue the fight.

############################################

If you enjoyed this article, I’d love it if you could hit the little heart to recommend it to others. After that please feel free email the article off to a friend! Thanks much.

###########################################

A bit about me: I’m an author, engineer and serial entrepreneur. During the last two decades, I’ve covered a broad range of tech from Linux to virtualization and containers.

You can check out my latest novel, an epic Chinese sci-fi civil war saga where China throws off the chains of communism and becomes the world’s first direct democracy, running a highly advanced, artificially intelligent decentralized app platform with no leaders.

You can get a FREE copy of my first novel, The Scorpion Game, when you join my Readers Group. Readers have called it “the first serious competition to Neuromancer” and“Detective noir meets Johnny Mnemonic.”

Lastly, you can join my private Facebook group, the Nanopunk Posthuman Assassins, where we discuss all things tech, sci-fi, fantasy and more.

############################################

I occasionally make coin from the links in my articles but I only recommend things that I OWN, USE and LOVE. Check my full policy here.

############################################

Thanks for reading!